The origins of Beatrix Potter's beloved tales

Peter Rabbit, Tom Kitten, Squirrel Nutkin, Jeremy Fisher – the beloved characters created by children's author and illustrator Beatrix Potter (1866-1943) have occupied a cherished place in the cultural imagination since the early 1900s. But what of the origins of the bestselling children's books? "It is much more satisfactory to address a real live child," Beatrix wrote to a friend in 1905, "I often think that that was the secret of the success of Peter Rabbit, it was written to a child—not made to order." Indeed, the (mis)adventures of Beatrix's pet rabbit, Peter Piper, were first recorded not in a book, but a series of illustrated letters to a little boy, Noel Moore.

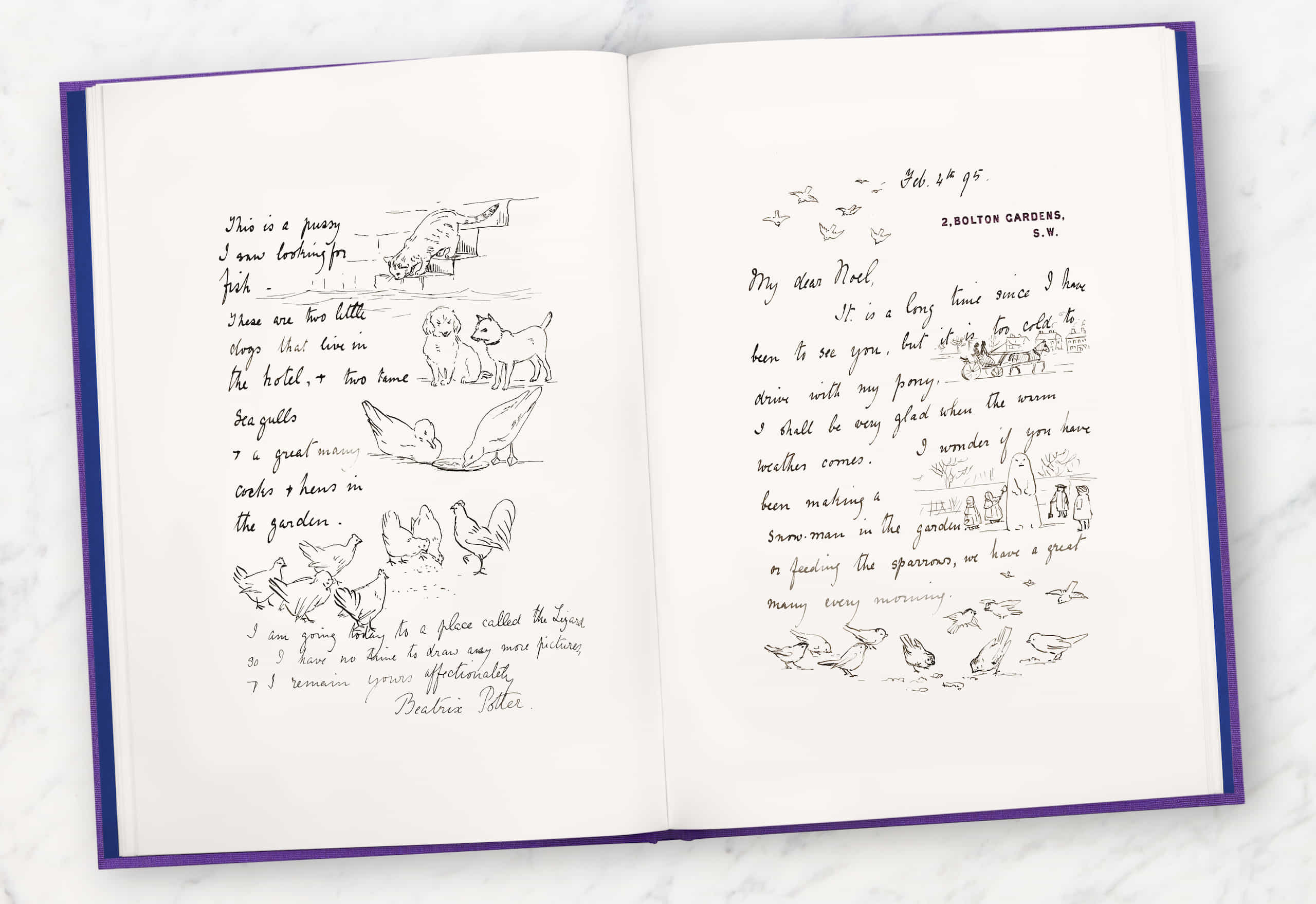

The letters that Potter wrote to Noel, his siblings, and other children she knew, embellished with endearing drawings of the scenes described, have come to be known as the 'picture letters.' In this volume, 12 of these picture letters – those held by the Morgan Library in New York – are published for the first time in a large format facsimile edition.

The letters are introduced by Philip S. Palmer, curator at the Morgan Library and a Potter specialist.

Beatrix before Beatrix Potter

Beatrix Potter was born in London in 1866 to a creative, upper-middle-class family. Her father Rupert, though a lawyer by training, was an accomplished amateur photographer, while her brother Bertram was a landscape painter. Holidays in the countryside of Scotland and the Lake District encouraged Beatrix's interest in natural history, while her and Bertram passed their time at home collecting plant and animal specimens and caring for their many pets. A fan of watercolour painting, Beatrix made finely detailed and anatomically correct studies of the animals she encountered, lending her later illustrations their dynamic, lifelike quality.

Like other young people of her family's social standing at the time, Beatrix was raised by a series of governesses at home, the last of whom, Annie Carter, was only a few years older than her. The young woman, who was 17 years old at the time, initially bristled at the idea of having yet another governess at her age, but the two women developed a close companionship which lasted even after Annie left to marry the engineer Edwin Harry Moore. The Moores had eight children: Noel, Eric, Marjorie, Winifrede, Norah, Joan, Hilda, and Beatrix. Noel, the eldest, was the most frequent recipient of Beatrix's picture letters, and received eleven of the letters presented in this volume, while the twelfth is addressed to his sister Marjorie.

Picture Letters: 12 beautiful manuscript letters with drawings

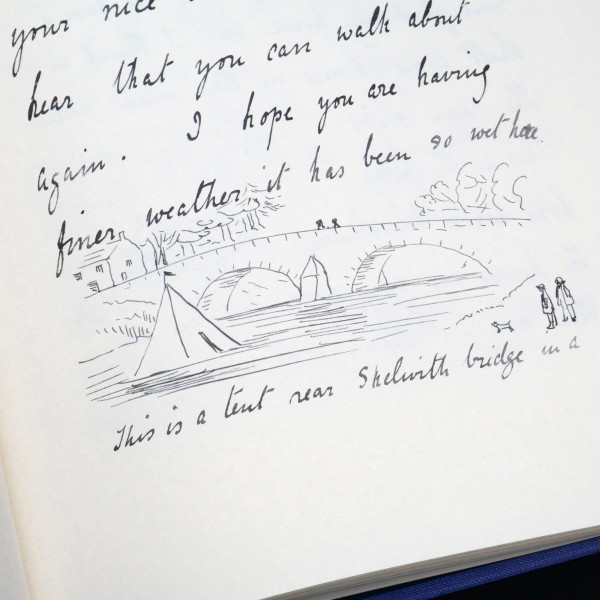

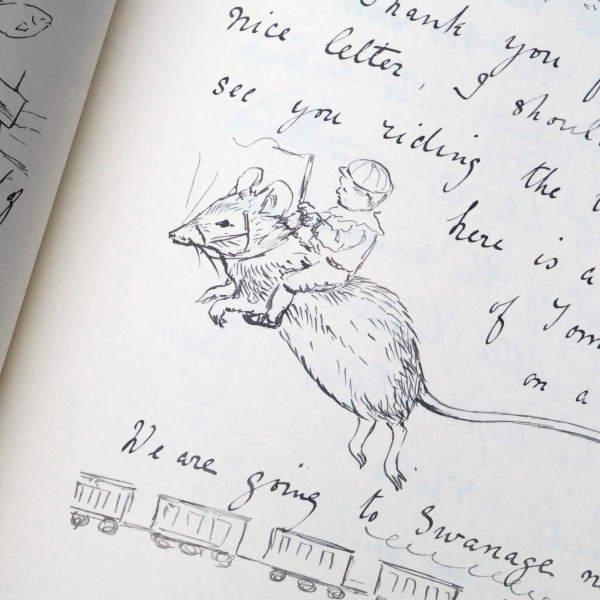

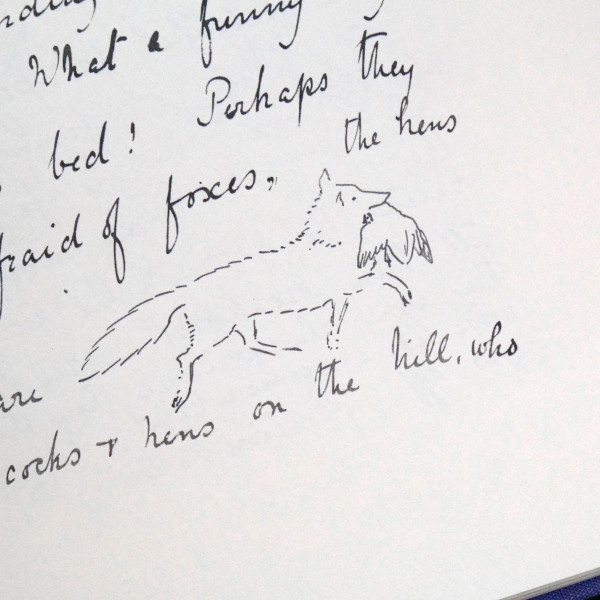

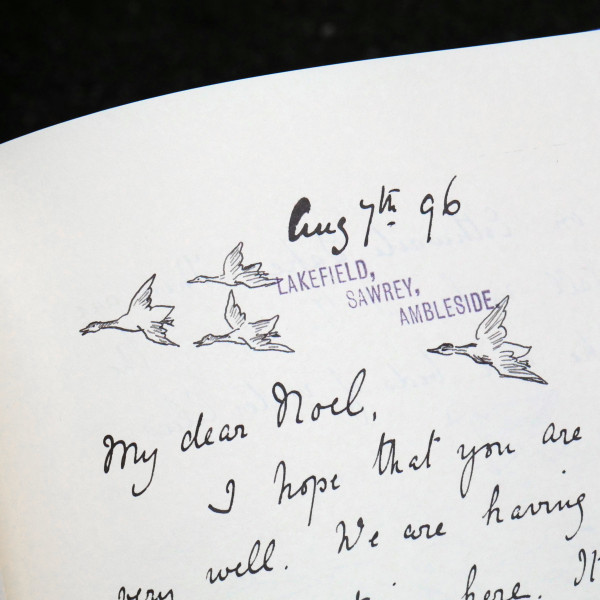

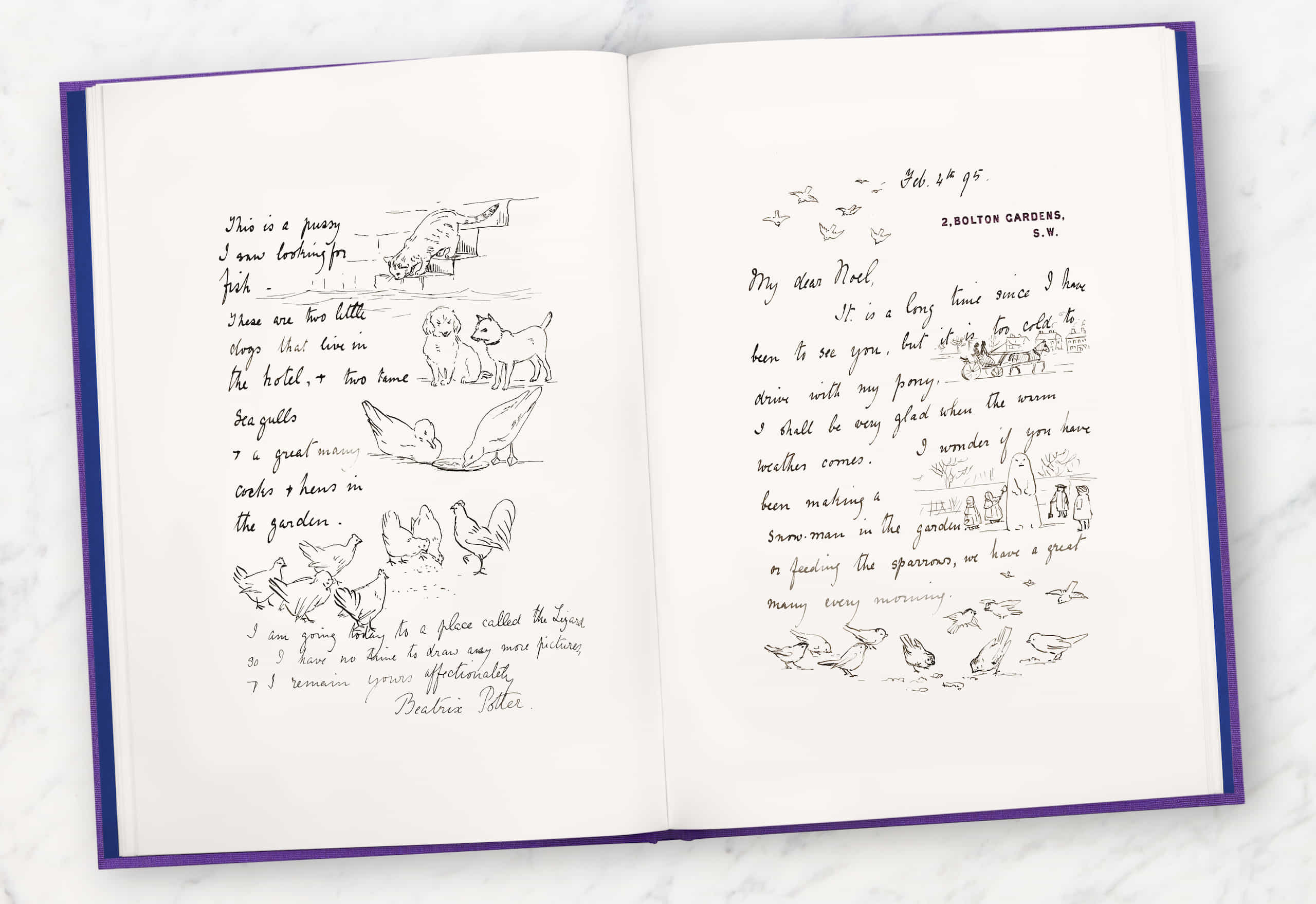

The twelve picture letters held at the Morgan Library are full of warmth, affection, and a keen sense of how to address and entertain children. Written between 1892 and 1900, they often feature an encounter with the animal world, whether during a Potter family holiday or a visit to the zoo. Through her inventive illustrations and her ability to transform a daily encounter into a tale worth telling, Beatrix establishes herself as a burgeoning children's author and illustrator.

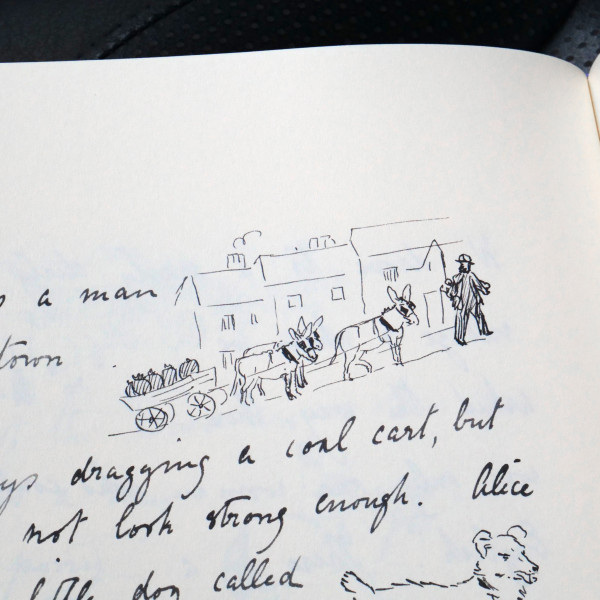

In her first picture letter, sent to Noel from Cornwall in 1892, Beatrix describes a cat "looking for fish," "two tame seagulls" and the "two little dogs that live in the garden," all accompanied by lively drawings of the scenes. In another letter sent from the Lake District, rabbits, hens, fish and donkeys feature alongside Beatrix's simple yet playful description of her holiday. Honing her ability to blend prose with illustrations, a blueprint for Beatrix's future stories emerges.

In February 1895, Beatrix recounts the habits of her rabbit Peter Piper, with the same ability to bring a scene to life. She explains, "He sat quite still and allowed me to [cut] his little front paws but when I cut the other hind foot claws he was tickled, & kicked, very naughty." This account is enlivened with a series of small sketches, including one showing those naughty, kicking hind feet. In a March 1895 letter, Beatrix relies on her powers of imagination to comfort Noel, who was unwell at the time. In an endearing scene, a little mouse (i.e., Noel) is depicted ill in bed, its tail trailing out from underneath the sheets and attended to by a doctor, Mr. Mole, and his assistant Nurse Mouse. Once dosed with a healthful draught from his caregivers, the little mouse, Beatrix hopes, "will soon be able to sit up in a chair by the fire." By blending scientifically accurate animal drawings with inventive and heartwarming tales, Beatrix established herself not only as a talented illustrator, but as a gifted writer.

From letters to stories

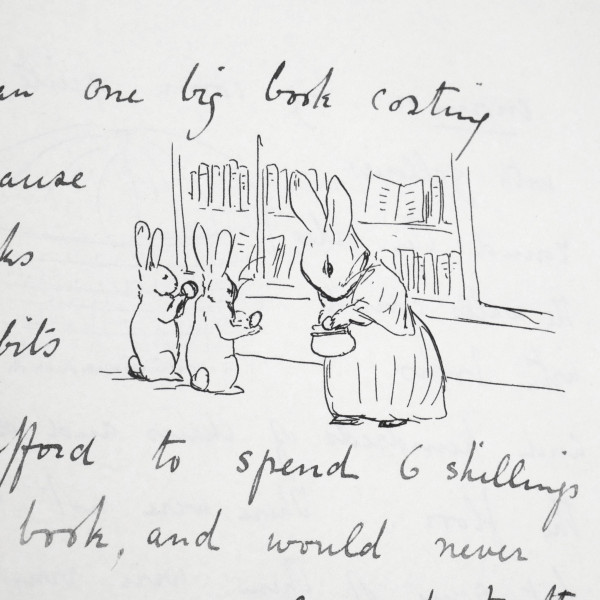

In around 1900, and having already sold several illustrations to various publishers as a way to make money, Potter borrowed back several of her letters to Noel with the aim of publishing her own illustrated children's stories. Her letter to Marjorie (the final in this volume) explains the difficulties she encountered. As Beatrix shows in the letter's drawing of a mother rabbit and her children outside of a bookstore, she wanted "little books" that were affordable to "little rabbits," who she thought would never buy bigger, expensive volumes. Indeed, the portable, child-sized format has been central to the enduring charm of Potter's tales for children. Eventually, a story based on one of her letters to Noel (now at the Victoria & Albert Museum, London) was accepted by Frederick Warne & Co, and The Tale of Peter Rabbit became an instant success, ushering in a prolific writing career that spanned into the 1910s.

The Morgan Library

The group of picture letters reproduced in this book were donated to the Morgan in 1959 by the book collector and army colonel David McCandless McKell, who became involved with the Morgan as a Fellow and subsequently served on the Morgan Library Council, eventually donating the twelve Beatrix Potter picture letters to the library in 1959. They are stored today in the Morgan's vault and continue to delight visitors from around the world, most recently in the 2024 exhibition Beatrix Potter: Drawn to Nature, organized with the Victoria & Albert Museum in London and the UK's National Trust.

Deluxe edition

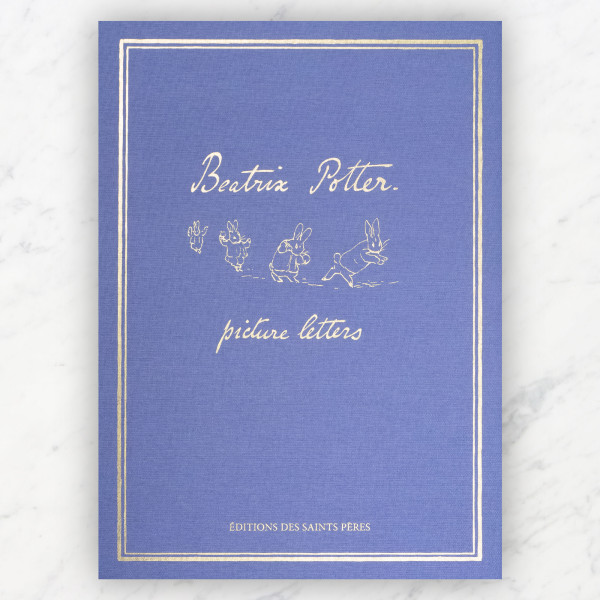

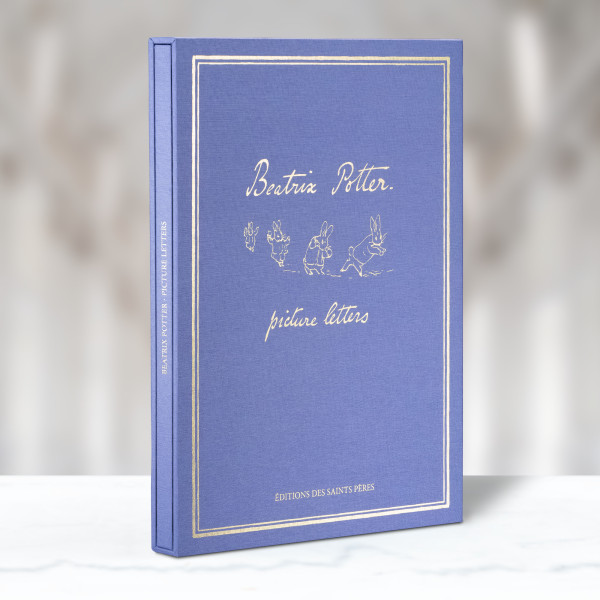

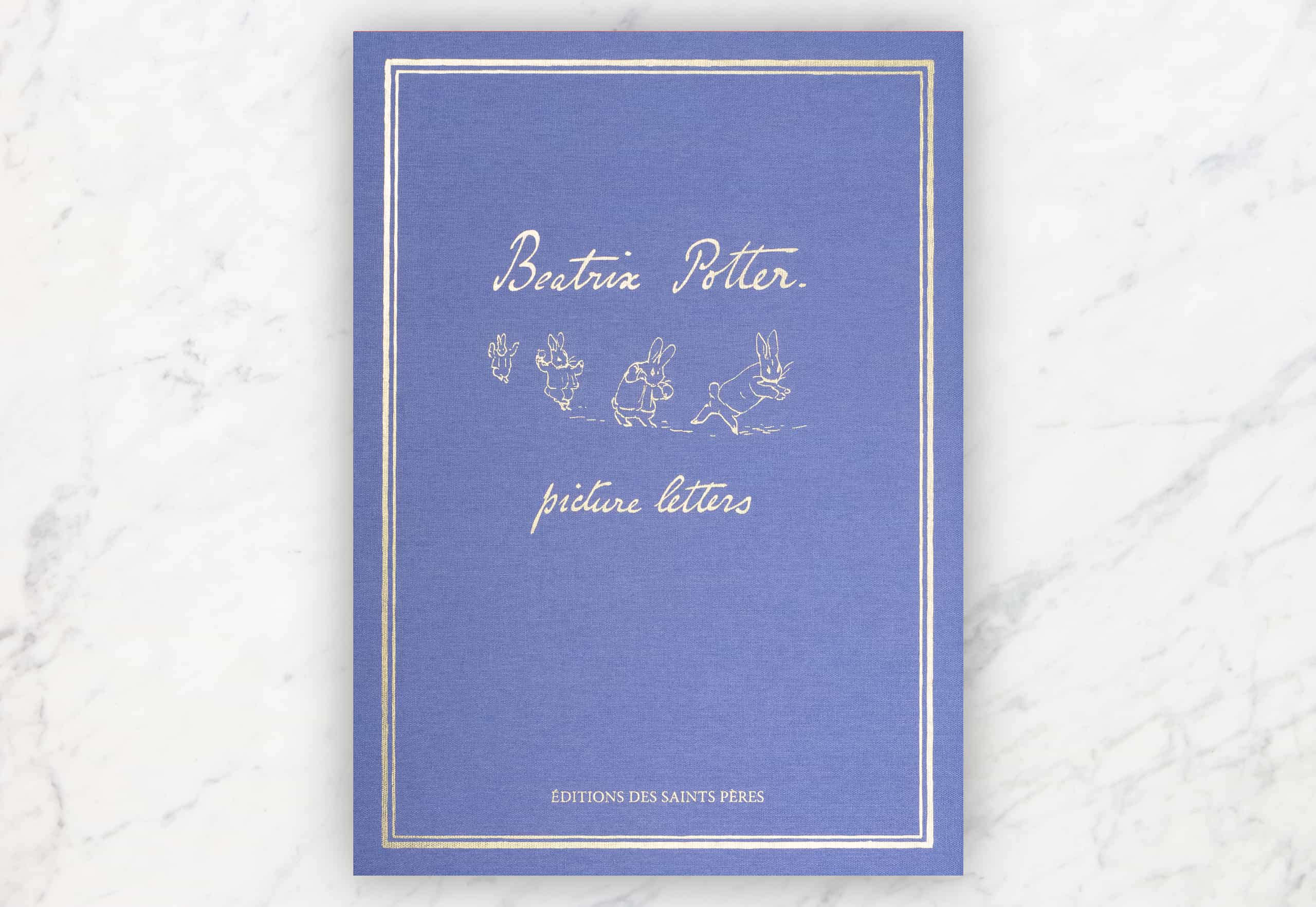

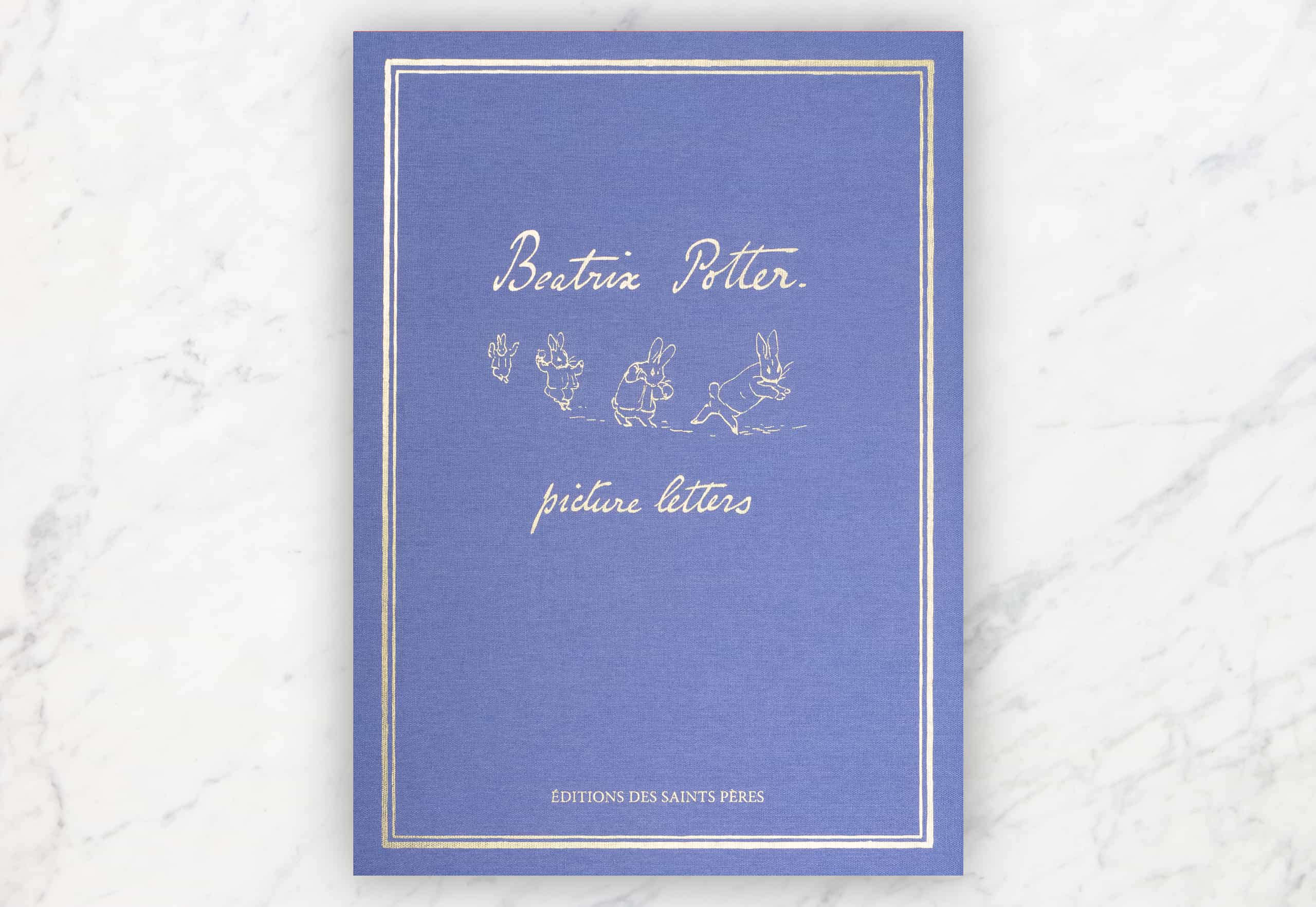

Numbered from 1 to 1,000,

this Lavender blue edition is presented

in a large format handmade slipcase.

Printed with vegetable-based ink

on eco-friendly paper, each book is

bound and sewn using only the finest materials.

Lavender blue edition

1,000 numbered copies

72 pages - 10 x 14"

Fedrigoni Deluxe Paper

Handmade slipcase

ISBN: 9782494080058

![]() Free shipping

Free shipping